Above: During my graduate years, I spent many hours at the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice working on my dissertation on Petrarch and Bembo and early transcriptions of Petrarch Italian poems.

Between the two working legs of my recent trip to Italy, I had just two days free over a weekend, when I could do whatever I wanted to do. What did I do? I went to a library, of course! And not just any library: I spent a truly sinful and decadently fulfilling morning of quiet study in the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana in Venice (that’s the entrance above), one of my favorite places in the world (where I conducted much of my research for my doctoral thesis back in the day).

In all honesty, I didn’t find what I was looking for that day but I did find a few clues that led me to what I believe is definitive proof that the Greek wine Vinsanto gets its name not from the Vin Santo of Italy but rather from the toponym Santorini, the island where it is made. (Here’s the link to my original post on the origins of the two enonyms.)

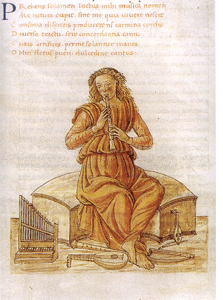

Above: My beloved Petrarch (1304-1374, subject of my doctoral thesis) bequeathed his library to the Biblioteca Marciana (named after the patron saint of Venice, St. Mark). A bust of Petrarch surveys the main reading room.

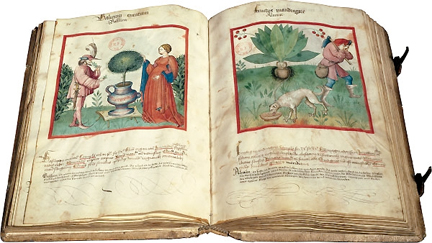

My research that day led me to the discovery of a fascinating 19th-century journal entitled, New Remedies, an illustrated monthly trade journal of Materia Medica, Pharmacy and Therpeutics (New York, William Wood, 1880).

In it (volume 9, page 6), I found the following passage (boldface mine):

- Greek Wines.

Greece, and particularly the islands of the Archipelago, produce a great variety of excellent wines, which have lately attracted the attention of eminent therapeutists in Europe. The most favored island is Santorino, the ancient Thera or Kalliste, being the most southern island of the group of the Cyclades, and belonging to Greece. A variety of wines are produced there, both red and white. The best red wine is called Santorin (or Santo, Vino di Baccho), representing a dry fine-tasting claret, with an approach to port. Another fine (white) wine is called Vino di Notte (night wine). There are two varieties of this, one named Kalliste, being stronger and richer; the other, called Elia, somewhat weaker, but both possessing a fine bouquet and equal to the best French wines, particularly for table use. The “king” of Greek wines, however, is the Vino santo, likewise produced in Santorino, occurring in two varieties: dark-red and amber colored. This wine is sweet, rich, very dry, and has a strong stimulating aroma.

Note how the author (Xaver Landerer, a professor of botany at Athens) refers to a wine called “Santo” and he refers to the island as “Santorino” (and not Santorini). Note also how he calls the sweet wine “Vino Santo” and not Vinsanto or Vin Santo (where the o of vino has been naturally elided by the inherent system of Italian prosody).

Together with the above document, I found numerous others from the same era that refer to a “Vino Santo” or “Santo” from “Santorino,” the common name for Santorini in the late 19th century.

I also discovered the following information, which I have translated from the Italian, from the “Summary of previously unreported statistics from the Island of Santorino, sent to the Royal Academy of Science of Turin by Count Giuseppe de Cigalla,” published in the Memorie della Reale Accademia delle Scienze di Torino (proceedings of the Royal Academy of Turin, serie 2, tomo 7, Torino, Stamperia Reale, 1845).

- Vineyards produce the [island’s] principal crops, with more than 50 varieties of known vine types. [68]

…

[In 1841 Santorini produced] Vino santo 2,350 barrels, 1,922 hectoliters, value 63,168 Italian lire [68]

The only product exported from Santorino worth mention is wine. The quanity exported in 73,120 barrels (59,797 hectoliters) was nearly in 1841 but it generally does not exceed on average 45-50,000 barrels per year (from 36 to 40 thousand hectoliters), correspondent to the amount of consumed in Russia. [70]

Evidently, Vinsanto from Santorini was widely popular in Russia, where it was consumed as a tonic (I found other texts that spoke of the wine’s popularity in Russia).

Above: My good friend and college roommate Steve Muench accompanied me that day and took this photo. A good Texan cowboy hat comes in handy in the Venetian rain!

Why do I do this? And why do I travel to Venice from Padua on a rainy Saturday morning only to spend 3 hours inside a library? As my friend Andy P likes to say, I am a self-proclaimed lover of Italian wine and a moonlighting Italian wine historiographer.

Even better news (for Italian wine geeks out there): I have also discovered what may be the earliest document (early 1700s) to make reference to Italian Vin Santo and the process employed to produce it. Ultimately, I believe that Vin Santo has its origins in the Veneto rather than Tuscany and you’ll see why when I post my findings later this week…

If you made this far into the post, thanks for reading! Stay tuned…

Yesterday on the Twitter,

Yesterday on the Twitter,  It’s also possible that Sangiovese comes from sangiovannese, an ethnonym denoting an inhabitant of

It’s also possible that Sangiovese comes from sangiovannese, an ethnonym denoting an inhabitant of

First of all, a little history.

First of all, a little history.