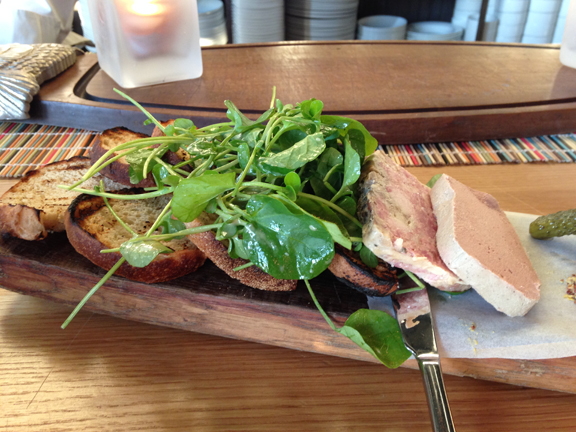

Above: Monforte d’Alba, where some of the greatest expressions of Barolo are produced, fall, 2012 (photo by David Berry Green).

It’s one of those linguistic questions that comes up often in my world: what is the proper English pluralization of Italian wine names like Barolo, Brunello, Barbaresco, and Prosecco, Italian proper nouns that end in <o>?

A few days ago, when one of my favorite Italian wine bloggers, the amazing Ken Vastola (check out his super cool site), asked me to share my thoughts on this conundrum, I decided to sit down and right a proper post about it (excuse the paronomasia).

Technically, enonyms ending in <o>, like those above (and all enonyms, for that matter), are singular, masculine, invariable nouns in Italian grammar. And as invariable nouns, their plural and singular forms are the same.

But many Italians will pluralize them based on standard inflection. Just as the plural of pomodoro is pomodori or cannolo is cannoli, where the final <i> makes the words plural, it’s not uncommon to find inflections of wine names like Baroli or Brunelli.

And similarly, English-speakers will commonly pluralize them as Barolos or Brunellos.

There’s nothing “incorrect” about inflections like these: the “correctness” of grammar is ever shifting and the evolution of language is based not on an unattainable ideal but rather practice and usage.

Thirty years ago, there were very few English-speakers in the U.S. who would wonder what the correct plural of Brunello was, let alone know that Brunello was a prized wine. Today, wine lovers, wine merchants, wine writers, and editors are often challenged and sometimes vexed by the question of how to pluralize Brunello.

“I tend to prefer the latter,” traditional style of the wine, wrote Jay McInerney on his Wall Street Journal blog in 2011, “although it’s hard to resist the upfront appeal of some of the more modern Brunelli.”

Would he have been faced with the issue in 1984 when he published Bright Lights, Big City?

I stand by my observation that this and similar inflections are not “incorrect.”

But they are best to avoid.

The reason is that this type of hypercorrective inflection often distances the word itself from its intended meaning.

In the case of Barolo, for example, the enonym is a toponym, a unique place name: Barolo, the village in Cuneo province, Piedmont. When hypercorrectively pluralized as Baroli, the toponym becomes cacophonous (the opposite of euphonious) to the Italian speaker.

The same holds for Prosecco, which is also the Italian name of a village, Prošek in Croatia.

If, for example, you were writing about a flight of wines made from Cabernet Sauvignon grown in Napa Valley, California, you might cacophonously abbreviate the grape name Cabernet Sauvignon as Cab (cacophonous, at least to my ear). But it’s unlikely that you would hypercorrectively pluralize the place name Napa as Napas. It would — more likely than not — sound strange to you.

There are also instances where the enonym is a homophone in Italian.

Barbaresco is the name of a village. But in literary Italian, barbaresco can also mean barbarian or barbaric. To pluralize the wine name as Barbareschi (where the <h> is needed to retain the velar consonant in the pluralized inflection of co; pronounced koh and kee respectively), not only corrupts the toponym Barbaresco but it also creates a superfluous homonym.

If you said, “last night I drank two Barbareschi,” to an Italian speaker, it would sound as if you were saying, “last night I drank two Barbarians.”

In my view, the best way to address this issue is to avoid it gracefully.

In my writing, you’ll often find instances where I use the phrase expressions of Barolo to avoid the wine name’s pluralization: “Monforte d’Alba, where some of the greatest expressions of Barolo are produced.” Bottles of or bottlings of are other common solutions to the problem. And there are plenty of other ways that writers can avoid this type of hypercorrection.

As I wrote above, it’s not “incorrect” to say Baroli but it’s preferable to avoid it (the pluralization of euro as euri, as opposed to sing. invar. euro, is an analogous example where both usages are accepted in standard Italian grammar, but the former is preferable).

Just think how a hypercorrective inflection of Montepulciano d’Abruzzo would sound to an English speaker or Italian speaker, where the wine name includes a grape name and two place names (one homophonous). Montepluciano d’Abruzzos? Monteplucianos d’Abruzzo?

A mouthful better suited for the palate than the pen (or keyboard, as it were)…