Above: Angiolino Maule didn’t know us from Adam and Eve when I called him in January asking if we could visit his winery and vineyards. By the end of the visit, we had become fast friends (sometimes it helps to speak Italian with a Veneto accent!).

If you follow along here at the blog, you know how much we love the wines of Angiolino Maule. They’re delicious and they’re affordable. And, in the words of the winemaker, they’re made with the utmost respect for Nature (with a capital N).

The story of how he went from factory worker to pizzaiolo to winemaker to Natural winemaker has been told many times before. The only thing I’ll add to it is that in an earlier time in his life, Angiolino was a gigging saxophone player and he loves music. When Tracie P, Alfonso, and I went to taste with Angiolino and family recently, the house was filled with music — speed metal, on the day we visited, preferred genre of son Francesco. The Maule family loves music and nearly every member plays an instrument and there were musical instrument strewn about the house. And you imagine our shared delight when, over dinner at Angiolino’s brother-in-law’s pizzeria I Tigli, we realized that famous Veneto jazzer Ruggero Robin is a close mutual friend.

Above: A stone wall in Gambellara reveals the volcanic nature of the subsoil. Note the wide pores of the red stone.

Although he also grows a few red grapes (more for professional pride than for any other reason, he said), his estate is about Garganega (if you have trouble pronouncing the grape, click here for the Italian Grape Name Pronunciation Project). His farming practices and winemaking methods are impeccably natural and he went to great lengths to explain to us how his growing sites are regularly tested for the residual presence of farming chemicals. Not only does the farmer have to eliminate the use of chemicals in order to grow Natural wine, he explained, the grape grower must also ensure that there is no chemical runoff from adjacent farms. He exclusively uses vegetal (as opposed to animal-based) composts to “re-pristinate” the nitrogen and carbon balance of his subsoils and he is actively engaging the academic community in an attempt — the first, he claims — to provide scientific evidence of how Natural winegrowing works.

Above: “When you take something from the soil, you have to give something back,” said Angiolino as he explained the application of vegetal compost to revive the microorganisms needed to achieve balance in his subsoils. While no one truly understand how the Natural chemistry works, Angiolino is working with university researchers to provide new empirical insight.

“We [Natural winemakers] are like the prostitute who marries the most upright boy in the village,” he told us, using an old adage to explain his expanding relationship with academia. “We need to make sure that the husbands’ shirts are ironed and that the children get to school on time so that the townsfolk will begin to take us seriously.”

But perhaps the greatest revelation that day was his method for unsulfured wine, i.e., wine to which the winemaker adds no sulfites, using only the natural components in the wine (sulfur is a natural byproduct of fermentation, btw) to preserve the wine and prevent oxidation.

The secret? He bottles directly from cask, using a syphon (a “straw,” he called it). He introduces the syphon into the cask through the bunghole and then lowers it to the center of the cask. He then begins to draw off the wine and bottle it directly. In this manner, he explained, the wine does not come into contact with oxygen and thus oxidation is avoided. (I know another winemaker in Slovenia who uses this method for bottling, although with a much more elaborate setup; you can guess who.) When racking (moving wine from one vessel to another), the resulting oxidation can only be corrected using sulfites, i.e., engineered SO2. (Sulfuring in wine is not a bad thing, btw… Over sulfuring wine is the bad thing. 99.999999999% of the wine you drink, even the finest wine, is sulfured. The truth is that without the use of sulfur, we wouldn’t be able to enjoy fine wine today.)

The other secret? Angiolino sulfurs the wine that lies at the bottom of the cask: at a certain point during the bottling process, enough oxygen enters the cask to cause slight oxidation and Angiolino minimally sulfurs that parcel to stabilize the wine. He rigorously labels his wines with a reporting of the alcohol, acidity, and sulfur content on the back label. Only his unsulfured wines report “NON CONTIENE SULFITI” (“does not contain sulfites”).

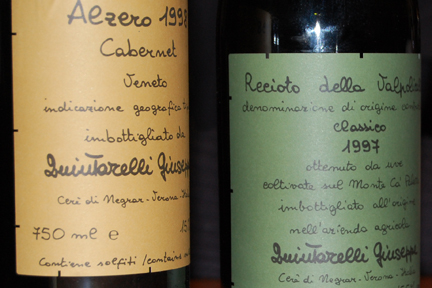

Above: Angiolino’s life and winemaking are about honesty. He is open and upfront about everything he does, feels, thinks, and believes. He talks very frankly about why he broke away from Vini Veri, which he helped to found, and how he regulates his VinNatur group with an authoritarian spirit. His wines aren’t for everyone. We love them.

There was another revelation that has been the subject of a lot of debate and discussion in our home.

At a certain point, Tracie P asked Angiolino how a Natural winemaker can avoid contamination by pharmaceutical yeasts, especially in an appellation like Gambellara, where industrial commercial winemaking dominates the landscape. “Is it possible,” she asked in her Neapolitan-cadenced Italian, “for yeast from the Zonin winery at the bottom of the hill to float its way up to your cellar?” (As lovers of Natural wine well know, one of the main tennets of the category is the exclusive use of native (also called wild or ambient) yeasts in fermentation.) If you’ve ever looked into Tracie P’s beautiful blue eyes, you know that it’s impossible to tell her a lie.

Angiolino paused and said, “that’s a very good question.” He paused again.

“When I first started making wine, I used cultured yeasts in my winery. The truth is,” he said, “once you’ve used cultured yeasts in any environment, they remain present. They never go away.”

Wow, this was a heavy moment for all of us. It called into question everything that we’ve been taught by the cultural purveyors of Natural wine. If only on an epistemological level, this revelation begs the question: is it even possible to make a wine using only native yeasts when pharmaceutical yeasts are present all around us?

In other words, is there such a thing as a 100%, purely wild fermented wine? Does the residue from previous vinifications (even Beppe Rinaldi conceded that he’s used cultured yeast on occasion) eliminate the possibility of a 100%, purely wild fermented wine? Does the yeast residue that travels on the shoes of a cellar worker contaminate a cellar forever?

It’s important to keep in mind that there’s a big difference between the use of “killer” yeasts that impart specific flavors through widespread application during fermentation (think California style) and neutral yeasts, applied sparingly and with forethought, to encourage and speed fermentation (Consider that Bruno Giacosa and Mauro Mascarello openly and regularly use neutral yeasts and Aldo Vacca uses a cultured yeast called “Barolo strain” that replicates the native yeasts of Langa — I’ve asked each of them directly.)

Do Angiolino’s wines meet the Natural wine dogmatists’s lofty requirements? I believe they do. Is truly Natural wine, as they define it, possible? I’m not sure anymore. Do Tracie P and I tend to like self-defined Natural wines more than others? Most definitely. Is Natural wine more about being conscious of how commercial and industrial winemaking changed the world of wine in the post-WWII era than it is about oxymoronic dogma? The answer surely probably lies somewhere between the Zonin factory in the village of Gambellara and the Biancara winery at the top of the hill, where Angiolino makes “magical music in a glass” (according to the importer’s glistening marketese).

The only thing I know for certain is that I admire Angiolino immensely and we love his wines. I love them because they taste real to me. They taste of rocks and fruit. They taste like my beloved Veneto. The speak a language that I understand. And when Tracie P and I share a bottle, we are happy — even happier remembering Francesco’s speed metal that day.