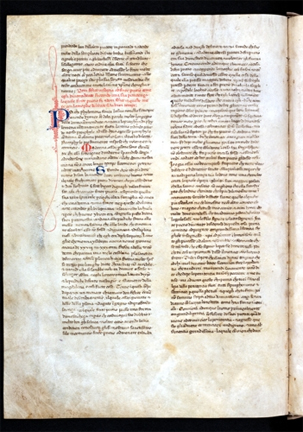

Above: Hamilton 90, the Boccaccio “autograph” manuscript, from the Staatsbibliothek in Berlin. Image via Quirinale.it.

In the world of rare books (a world I used to inhabit in my academic days, when I studied and wrote about Italian incunabula and humanist amanuenses), most “special collection” libraries observe the same protocol when two scholars request the same manuscript or codex on the same day: the librarians give the manuscript to neither.

One of the most notorious anecdotes from my days as a student of scribes was that of two illustrious Italian professors — one Italian, one American — who competed to discover the earliest autographed redaction of Boccaccio’s Decameron, in other words, his first “authorized” version of the work, transcribed in his own hand (a holy grail among philologists and paleographers like myself).

When the one professor discovered that the other was headed to the library in Berlin to request a viewing of the vellum, he raced to arrive before his colleague and he swiftly put in a request to view it as well. As a result, the librarians gave it to neither that day.

Ultimately, the one professor stole the manuscript, took it to Rome, had it x-rayed, and became the first to prove its connection to the fourteenth-century author. He replaced the manuscript before anyone noticed.

Not long after, the other professor killed himself.

That’s a true story.

There’s a saying in academics, the competition is so fierce and the enmity so ferocious because the stakes are so low.

And the same can be said about wine writing.

Above: Codex Hamilton 90 is currently on display in Rome, in a show organized by the Italian government. That’s Italy’s first two-term president, recently re-elected Giorgio Napolitano (left), viewing the show. An article devoted to the show appeared in today’s edition of Repubblica.

One of the ugliest episodes in the history of oenography has been playing out over recent months, with Montalcino as its backdrop.

If you haven’t been following along, the Brunello consortium announced last week that it was expelling and suing one of its members for defamation. (Here’s a link to my post on the legal action; it includes links to my reporting of events that led up to the consortium’s move).

December 2012: Soldera’s winery is vandalized; six vintages purportedly destroyed.

December 2012: Consortium offers to donate wine to Soldera winery out of solidarity.

March 2013: Soldera accuses consortium of encouraging him to commit fraud when offering to donate wine; announces he’s leaving consortium; announces that he’s recovered a good quantity of wine and that he plans to sell it.

If Gramsci Pasolini Marx were alive today, he surely see the situation in Montalcino as a text-book example of his theories.

In the 1950s and 60s, Montalcino was still an agrarian economy, with a few patrician families — like Biondi Santi — who served as stewards of its production of fine wine.

In the late 1960s, “big wine” arrived: American-based Banfi set up shop, not to produce Brunello but rather to produce sweet sparkling wine (Moscadello di Montalcino).

In the 1970s, Soldera, a rich Milanese insurance broker, who was unable to acquire property in Piedmont, bought land in Montalcino and started to produce fine wine.

By the 1980s, Banfi had shifted to the production of Brunello and helped to make Montalcino as a brand in the U.S. through high volume and aggressive marketing.

There were many other players in this equation but these two more than any other reshaped the way Brunello was perceived beyond Montalcino’s borders. And in doing so, they changed the way that the Montalcinesi viewed themselves.

On the one hand, Banfi opened up the world’s largest markets to Brunello. In the 1960s, there were only a handful of Brunello bottlers. Today, there are more than 250.

On the other hand, Soldera transformed Brunello into an extreme luxury product, delivering bottles that fetched astronomical sums.

Along the way of this dichotomy, Montalcino passed from de facto feudalism to full-throttle capitalism.

And the tension that has come to a head here is, in many ways, a dialectic held taut by a battle between agrarian and capitalist values, with indigenous growers on the one side and outsider financial interests on the other.

Add to this mix that Soldera is generally considered a carpet-bagger (he is) and that his cantankerous personality and his unbridled egotism have won him few friends there. After years and years of acerbic commentary (public and private) from Soldera, it was only natural that a situation like this would arise (many in Montalcino predicted something like this in 2008, when it was rumored that Soldera had sent a letter to authorities igniting the Brunello adulteration scandal).

Let’s face it (and it’s high time that someone wrote this): when news broke that Soldera’s winery had been vandalized, many observers of the Italian wine world (myself included) couldn’t help but think, to borrow a phrase from Lennon, instant karma’s gonna get you.

Was the consortium right to sue him? It’s not for me to say or pass judgment.

Most on the ground in Montalcino believe that his “resignation” stunt in March was a means to let the world know that he had miraculously recovered wine to sell.

No one can know for certain. But the consortium and its members had to do something. If they didn’t, they’d be allowing the “broker from Treviso,” as the consortium’s lawyer has called him, to exploit their brand in the service of his own personal agenda (this is how many in Montalcino view the situation).

Does any of this matter? Maybe to Marxists like me. The bottom line is that the renewed controversy has only helped to keep Montalcino in the news. And as any public relations veteran will tell you, all news — even bad news — is good news when it comes to raising awareness of your brand.

In other news, over the weekend, newly elected president Giorgio Napolitano, after a nearly three-month stalemate, ushered in a new government to be headed by political scientist and statistician Enrico Letta.

These political acrobatics (as the New York Times has called recent developments) are remarkable: Letta, center left, has emerged as “bridge builder” from a seemingly intractable deadlock, with the support of the most vitriolic opponents on either side of the aisle.

Only in Italy, some have said, shaking their heads (myself included).

But it’s all part of our my fascination with Italy and the enigmas of its greatness.

In the words of the great Harry Lime, “in Italy, for thirty years under the Borgias, they had warfare, terror, murder and bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci and the Renaissance. In Switzerland, they had brotherly love, they had five hundred years of democracy and peace — and what did that produce? The cuckoo clock.”